Winter, Out of Order

The kitchen sink is out of order again, drain water oozing, drop by drop, to the depths of the sink cabinet, and from thence into a widening lake on the floor. At some risk to himself, Frank battles the leak (the result of insufficient coupling). There is a natural enmity between Frank and plumbing; while he usually (eventually) wins, victory always comes at some personal cost– limbs, digits, psyche.

After this battle, he wears a bandaid.

I make Nora’s lunch in an early morning kitchen. Here, pre-dawn’s native dark is diffused by lamplight; the lamps serve this purpose exactly: to cut the new day’s electric intensity– its glare, as well as the effect of its rapid-fire hours– by half. In the slow-mo half light, I also try to at least half believe in the efficacy of my task, for Nora is difficult to please. Spoonfuls of unset jelly take its cues from the kitchen sink; it spreads in a flood across a width of peanut buttered bread. I try to dam the jelly’s progress by sandwiching another slice of bread on top of it. My effort is futile. Recognizing no boundaries, the jelly continues; it slides between the crusts, then onto and over the cutting board, and across the countertop. Go ahead, I tell it, noting its progress as I slice an apple. You, too, can try for the floor.

For As Long as We Can Remember

Nora wants a ball python. It seems she always has. At first, it is understood that I object, that asking for my permission is futile, and so the question lies mostly dormant, a thing Nora brings up only in her angstiest moments. Which moments increase rather than decrease over time because, since our recent move, Nora is a stranger sojourning in a strange land, without friends to comfort her, and only the occasional rock for a pillow in the dark mountainous night.

The ubiquitous tyranny of high school is amplified for Nora by hers being an unfamiliar one– thus her want of python pet grows even more. She is our last, and furtively measures the special powers of a youngest child against my objections to the snake (which objections are, in order of importance: Odor, Lack of Space, and Possible Death of Persons by Snake Constriction).

My finest objection– The Immorality of Buying Into a Culture That Breeds Wild Creatures for Life In a Cage– does not occur to me until it suddenly becomes irrelevant.

September 22, Exactly

Because at almost the very moment that my righteous indignation against animal caging is stirred to a final “no”, Nora gets a chance to rescue rather than purchase a ball python. Meisha, our second youngest, works at an animal shelter where the forsaken snake lands. Meisha breathlessly breaks the snake’s story to us in all its tragic detail: Faustus (this is the name Nora ultimately gives the snake) had been abandoned, along with several caged ferrets, in a vacated apartment. The ferrets perished, unable to survive those long, silent, empty weeks without food and water before they were too-late discovered.

But snakes are thriftier, and while Faustus is terribly emaciated and half-stuck in a thwarted skin shed, he is still alive.

His tragedy is irresistible to all of us. And so he comes to Nora’s room in a donated flannel pillowslip. We give him a glass castle, a heat pad, a hidey hole, very specific wood chips, and clean water.

Also, we buy tiny, frozen, dead mice. So that he will no longer starve.

Winter Blurred: January– Erstwhile February, March, Even April

Early mornings slip into a blur of days. Frank fixes the sink; I wrestle Nora’s lunches and my house chores into scant minutes, hasten my quota of steps in the park before the early sun crests the mountain. Knowing the time I’m winning for afternoon painting will still be jagged with unmet expectations and fear of failure, I tuck small sweet things– dark chocolates wrapped with purple foil– into sparkly blue glass jars, to discover later.

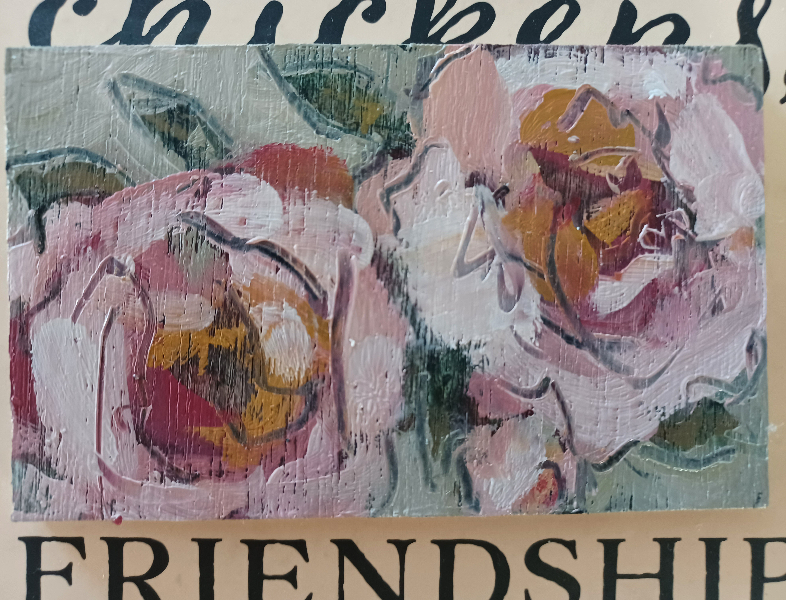

I suspect that it is somewhere in this winter blur that certain favorite citizens in my gardens catch cold and die. My Zephirine Drouhin rose (a Bourbon, bred to intoxicate with her raspberry fragrance in early summer) capitulates to winter’s inexorable advances. In April, a wrinkled rose cane the color of burnt sienna will break in my hand, brittle, from Zephirine’s ground level heart. In April I will run my fingers through a yellow crumble of young arborvitae needles, and they will shower, dry and lifeless, to the ground.

So there is no chance I could, in good conscience, set a ball python (native to SouthEast Asia and parts of Africa) free in such an intemperate environment, even in summer. Not that it doesn’t cross my mind; my sister’s summer garden in Central Oregon is bedazzled with reptiles, tiny lizards that flicker in and out of light and shadow, amiably munching on bugs.

A Few Fine Winter Days

While February alone plays hostess to Valentine’s sweet expectations, for me there must always be dark chocolate. Here and there, scattered amongst winter’s blurred days, is the glitter of purple foil wrappers.

A friend catches a glimpse of Nora in her car at an intersection, singing. Nora’s windows are down; she is alight in afternoon sun, swaying in the happy lilt of her own music. The friend tells me about this weeks later; her report of Nora’s joyousness invites a hopeful glow into the dim chapel where we stand talking amongst empty, shadowed pews.

Valentine’s Day

On Valentine’s Day, another friend wakes up and finds his wife cold. She is gone, his new old love, the girl that got away in high school and was found again in their middle age, his fresh hope against past heartbreak. I remember the day they married last November, how the chill wind in the parking lot lifted the hem of my skirt and nipped at my legs, how the groom was almost tearful in his joy when he greeted us. Bride and groom served cookies and a baked potato bar at the reception, displayed childhood pictures of each of them.

His daughter calls Meisha, for in times of crisis they are as close as sisters. “You must come and be with me,” she says. “My dad’s wife just died.” She is setting out for her father’s home when she calls. After she reaches him, she calls again. She has decided, in the depth and warmth of her father’s grief, that she needs to be with just him; Meisha’s company at this point would be superfluous. “But thank you Meisha,” she says, “for always being there for me.”

Before Valentine’s Day, a couple we know heads to the hospital on the other side of the mountain. I imagine it is early morning; she is in hard labor. It is snowing and traffic comes to a standstill in the mountain pass, perhaps because there’s a white-out— almost certainly because the roads are too slippery to continue on. The couple is marooned in their car on the edge of a dam in the storm; in the white flurry, the husband safely delivers the baby in the car (he happens to be a medical intern).

They post a video of the birth (and their gratitude) on Facebook.

Our bereaved friend also posts his gratitude on Facebook, for all the support and condolences he’s received. His daughter posts a new family mantra, something about getting through hard things together. In March there’s a picture of father and daughter, smiling at the camera. He looks thinner than I remember him.

Frank Does February

Every morning Frank wakes earlier than either Nora or I. He heads to the gym in his super cool Tesla (Frank finds an electric, moment-by-moment contentment, driving his Tesla). He listens to podcasts, tries the heft and resistance of weights, treads elliptically through space. His drive to and fro isn’t short; it includes climbing onto the shoulders of the mountain pass as well as descending into the fissures at its knees, but this is ok with him… more time for driving, listening, thinking; more opportunities to rescue random citizens.

Because occasionally people on the road break down, or slide off, or have babies. A middle aged woman swerves wildly and lands her car beyond the ditch in a snowy field; a young man (a boy, really) gets a flat and needs a ride.

The boy is trying to inflate his tire with a bicycle pump when Frank stops to help; the boy has been at it for a while by then, even though he knows his tactic isn’t working, that it never will. The tire’s puncture is discernible; he has seen it, as Frank sees it.

It is natural that one would feel desperate when one is stranded.

January is the Loneliest Number, and it is Cold

Scraps meant for compost fill a bucket outside the kitchen door: orange peels, apple cores, used tea bags, bits of darkened lettuce and celery– all stand stiff and at attention, all are laced with frost as if by a spreading crystalline mold. The trees at the park, usually beautiful in metaphor and grace, today are merely dead sticks reaching for each other and the sky, cold-blasted. Some twigs litter the path where I come to walk, their broken and crumbled widths like so many compound fractures, punctuated here and there with a scattering of bituminous deer droppings and the dessicated vomit of an over-eager, leash-resistant beagle (I have seen him at it, the vomiting, straining against his leash, his owner bemused, stumbling to keep up). The ground is bare, grey and brown, a crevassed rumple of iced mud, dead grass, and weeds the color of overused straw.

Large, sharp-edged snowflakes materialize in the dry cold air from nowhere; they drift from the vicinity of the mountain’s shoulder, over the stark reaching trees and into my anxious path, where they prick my cheeks and my eyes and disappear without a trace, not even a tiny wet mark.

I shift from peanut butter sandwiches to saltine crackers with ham and cheese, then beans and cheese and tortillas, then pita and hummus for Nora’s lunches. I beg her to take vitamins, sneak collagen and chia seeds into peanut butter. I am desperate to find something that will entice and then nourish her; her attitude towards lunch has devolved from apathetic to dismissive.

In my kitchen’s morning lamplight, I cannot blame her. I wouldn’t want to eat alone in a high school wilderness either.

And I don’t much like collagen and chia buried in peanut butter, it turns out.

Perhaps A Monday, Back in November

A girl in one of her classes at school learns that Nora has a ball python, and is immediately entranced. “Let’s be friends!” she exclaims. “I wish I had a ball python.” Though Nora feels a bit cynical and embarrassed about her new acquaintance’s reasoning and motives, she does exchange texts with her, chats with her in class. The girl brings a crocheted pouch to school and gives it to Nora. “For your snake,” she says. She hugs her.

Nora leaves the pouch next to Faustus’s glass castle on her bedroom floor; it lies there for weeks. Eventually I put it in the coat closet for safekeeping. I don’t know if Faustus has ever been in it.

Late February, Early March (Most Likely)

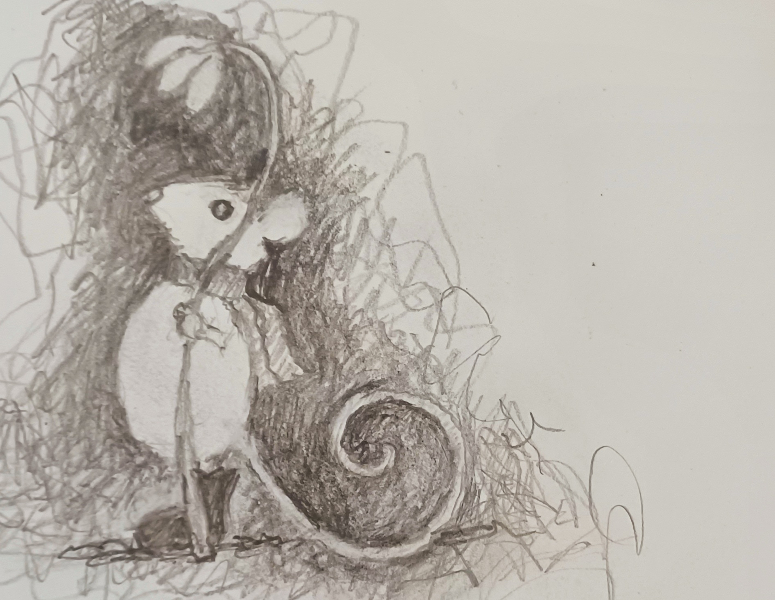

Nora says that she is anxious and depressed. I schedule appointments: first, with a neuropsychologist, and later, after the diagnosis (Nora is beautiful, intelligent, and generally anxious), with a counselor. The counselor invites Nora to draw her anxiety and depression, to personify and imbue them with shape and color. My daughter Maurya thinks this is a good idea; I think of Wendy from Peter Pan: “I do believe in fairies, I do, I do.” Or Oz’s Dorothy, in a sparkle of ruby heels: “There’s no place like home, no place like home.”

The little gray frame house, airborne from Kansas, that lights square upon a stripey-legged witch.

I keep trying to paint, of course not plein air, but from my own photos of the winter park and other nonsense I find on Pinterest (I have never painted outside, and February in Utah is hardly the time to begin). It is not going well; I am mostly just pretending to paint, swirling my brush in oil that’s gone sticky. Sticky paint is a particular indictment; good artists do not paint sticky. Still, I discover, entirely by accident, a lovely effect in an abstracted landscape… pink and gold light glowing out from behind muddy grey-blues… but then it is gone. I try to replicate it, chasing sequence, color, a turn of the wrist, a renewal of fresher paint… but really, it is gone. I cannot make it happen twice.

Wednesday, Late February

So preoccupied in paint am I that I miss the moment Nora drives away in the frosty afternoon, on an errand for mice for her snake. Euthanized mice, for she believes a live mouse defending its rodent existence could prove injurious to her pet. We have discussed this much, from a time of innocence, before the snake came to Nora, to the time when the snake was real and needing sustenance and there were tears because the mice Frank and I bought at Petco were insufficient. Nora, like exiled Hagar grieving for her thirsting son Ishmael, has become desperate about the feeding of her snake.

Meanwhile, I transform a painting mistake into something else, a possibility. Mop-headed trees, benign and wispy little monstrosities, straggle in a huddle up a sun-washed hill in a fierce burst of morning light. Impossible to tell the season… the colors are evocative of an exceptionally bright winter moment, but there is, after all, foliage.

Late December

The python coveting friend stops coming to school. She texts Nora that she and her family all have Covid; they are quarantined and of course it sucks. She worries about her dad, who seems particularly ill and doesn’t want to see a doctor.

Earlier in February, Perhaps Tuesday, Thursday

Being seventeen with an untried brilliance, Nora reaches for diplomacy about the insufficient Petco mice we’ve provided, but lands instead in a blizzard of breathtaking vexation… bitterness appearing suddenly out of nowhere– overblown, sharp-edged snowflakes materializing in thin air. Again and again, we three grapple to understand, persuade, find solutions, keep the peace and love. Frank calls these episodes Armageddon.

True, Petco mice are just pale cadaver blinks frozen in shrink wrap… but we assumed Petco knows what they are about. Don’t the masses feed their snakes this way? we ask each other. Foolishly forgetting that Nora will never identify or even politely agree with the masses. To her the Petco mice, like so many expired Twinkies, can only lead to a damaged or dead Faustus.

I think of the saltines I pack in Nora’s lunches, the ham and cheese and peanut butter and drippy jelly. Knowing that I haven’t resorted to Twinkies is small comfort.

I fantasize again about letting Faustus loose in the garden, to forage naturally for himself. But it’s just one more nonsensical thought; even if he could survive our extreme droughts and winter freezes, as a free garden citizen he would be incapable of honoring Nora’s notions of his role as her pet. She would likely never see him again… He might even grow large enough, in his secret garden hiding spots, to eat our cat.

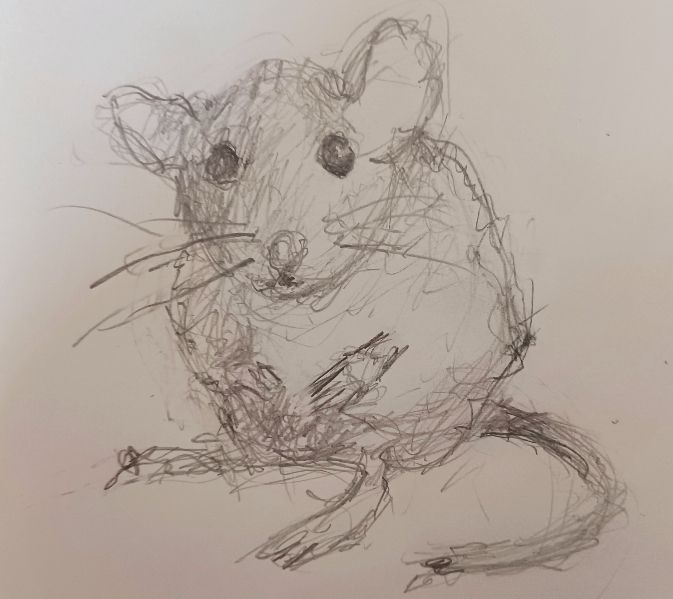

Then there is the moment a mouse is in my hand without my knowing it, one Nora has left on the countertop for just a moment while she boils water to thaw it in, one I have picked up blindly, unwittingly, during after-dinner clean-up– like a chocolate wrapper, orange peel, bread crust. I don’t know to scream until a stiff coldness penetrates my fingers and I look into my hand mid-stride and see that I am holding a small nightmare, a tiny frigid white corpse.

Early January

“I don’t know how to tell you this,” texts Nora’s python-loving friend, “But my dad died yesterday. He got too sick; he kept refusing to see a doctor.” Nora reaches for the right words, but there are none. She’s left with Petco/Twinkie quality options: I’m so, so sorry, that is so hard, what can I do, I’m here for you. “Thank you,” her friend texts back. Nora learns her address; we make chocolate chip cookies and drive with Nora to the house where the girl is staying. She and her mother and sister come out on the porch to receive the cookies and thank Nora. I am astounded at how people can walk and nod and wave and accept the insufficiency of mere cookies when they have just lost everything.

Back To The Wednesday in Late February That Nora Drove Away For Dead Mice

So Nora drives alone to a distant town to pick up the new, superior, executed mice, while I paint alone at home in disquietude. She returns with her necessary burden and a chilling tale; for in fact, to my ears, the exchange of money and goods through her car window at the curb of the anonymous mouse-breeder’s residence has gone down like a scene from a crime drama. I tell her next time we should go together to buy the snake snacks, and she shows me the spoils of her venture: eight dead mice in a large ziploc bag. My throat tightens in startled grief; Nora agrees that the mice are tragically pretty. They look so real. Aside from their uncanny stillness, they seem almost alive– a clannish gathering of smooth-furred brown and white cuties edged in pink, each curled affectionately around another, front paws held aloft like unfurled jazz hands. Their glossy black pin-button eyes are wide open, unblinking, staring out of the bag at nothing.

I paint more trees in a broken line against a pink sky. They are still in leaf, their foliage brown and grey. Pink light tumbles from behind into a greyish foreground. My imaginary critics tell me the trees aren’t recognizable as trees, necessarily, but maybe one day I will pull off a good abstract painting.

Northwest Passage Beginning, End of February

We leave home in a blanket of grey skies, to visit our parents in the Northwest. It is a long trip; we notice, crossing Idaho, that sometimes the earth is blanketed with snow, and sometimes it is not. Wondering about the disparities of Western precipitation, we listen to a podcast. And then a book.

The podcast muses about Abraham and Sarah, their wanderings and patience-won solace. I admire these ancient Hebrew protagonists– He is a centenarian and she is old enough that she cannot help but laugh when she learns she will at last be a mother.

The Hagar parts are sad to us, and complex; we cannot help but love her. We conclude for now (leaving doors open for other possibilities) that life is messy, conflict inherent, redemption’s alchemy crucial.

The book we listen to is The Book Thief. I adore the foster father, Hans Hubermann, his eyes that melt, in kind moments, to liquid silver, how he rescues traumatized Liesl from her nightmares by painting words she learns to read on the basement wall.

When we arrive at my parents, they feed us shrimp and salad, steak and tart berries; they’re gentle missionaries, proselyting a Keto lifestyle, and we luxuriate in their evangelism.

When we arrive at Frank’s parents, his father serves us carbohydrate-rich cheddar potato soup. He shows us the soup mix he used, to assure us of the ease with which he manages his cuisine. But he also has added his own touch, as he always does. This time, rather than a dash of Chalula or pepperoncini or flotillas of melting cheese, Chinese potstickers (from Costco, not China) sink deep into the potatoey cheddar gravy. Once again, I am surprised that his culinary exuberance manages, after all, the impossible. The soup and potstickers are actually edible… palatable, even. Perhaps because they are warm, and starchily bonded.

Back in January

The school friend invites Nora to her father’s funeral. Nora can drive herself, but she asks me to go with her. It’s the afternoon of a beautiful day; trees shrouded with snow capture the setting sun in glowing golds, oranges, pinks. The light streams through our car windows and caresses us as we drive. Nora is telling me things– her dreams and grievances, Biblical in proportion and feather-light in weight– when I realize I’m on a collision course with a bicyclist who is crossing the road ahead of me. I’m driving Frank’s Tesla; even so, the brakes lock up and the tires slide to within inches of the biker. He stops at our fender, waves at us, continues on.

We find seats in the mortuary chapel. During the funeral, there are stories about the deceased father, the chickens he launched, as a boy, from a garage roof (with parachutes, because he’d discovered in earlier launchings that chickens cannot really fly), the clunker car he outfitted with booming speakers, how he met his second wife at Big O Tire and treasured her to the end. I catch echoes of abiding love; it wrenches at me in ways similar to the transience of sunlight captured in snow, Hagar’s flights.

Someone begins to play a piece on the chapel’s piano. Just a few chords in, I know it; it is ours, my children and Frank and mine. Nuvole Bianche by Ludovico Einaldi, which sounds fancy but is intimate and sweetly haunting, a confectionary Will o’ the Wisp, a vanilla phantom. Meisha used to play it on our Gone With The Wind baby grand (which survived a fire and now belongs to Maurya). I open Marco Polo on my phone because it’s the only way I can think to capture it. Catching both Nora and myself in the camera, I whisper to Meisha, to all Frank and my children, through the phone, this is our song! Remember?

End of Northwest Passage, March (Armageddon for Reals)

We head south for home again Monday morning, slightly mournful. The beloveds we leave behind in the Northwest are as Sarah and Abraham to us, Hans and Rosa Hubermann. Just past my parents’ home on a mountain shoulder, the freeway turns to a flood of ice, and across the median, on the northbound side, we see the worst piled-up wreck we’ve ever encountered. The jagged mess is strewn pell-mell for miles: semis jack-knifed by the dozens on the road’s shoulders; passenger vans, cars, and trucks munched between Goliath freighters like so many crumpled table scraps: crackers, foil wrappers, orange peels… fenders, doors, hoods, carriages… the wreckage touches everything. We imagine the people we cannot see, their moments of collision, the stark aftermath, the altered realities. Emergency personnel have yet to arrive in critical numbers; the first walks slowly through the scattered tail of the metallic leviathan; a second stands in the middle of the freeze-frame interstate, taking pictures with his phone.

We see the first flashing lights a few miles beyond.

We look at the news, later, and learn that over 90 vehicles have been impacted. Two fatalities, many hospitalizations. A strange guilt haunts us, that we passed Armageddon so freakishly untouched, while innocent others did not.

Wednesday, Home in Mid-March: It Snows.

Grateful to be unscathed by winter travel, I walk with a friend at the park. Our steps together are lighter than mine are when I walk alone; we talk and laugh as stray snowflakes gather, combine, expand, multiply. These are gentle flakes, generous and without edges; they carry the calm hope of feathers and guardian angels, and quickly become a comforter that covers broken twigs, the rumpled grey-brown earth.

After school, Nora selects a new cute dead mouse to feed to Faustus, who finished molting the day before, and has been refusing to eat since well before the molt began. She is conscientious and tactful in this ritual; everything about the selecting, carrying, and thawing she does strictly behind the scenes. When she lowers the thawed mouse into the glass castle, she is careful not to startle the python. She holds still in time, dangling, dangling the mouse by its inert tail.

Unable to paint for days now, I watch television (a crime drama) with Frank after dark and draw faces and figures in my sketch pad with a ballpoint pen. The pen, for me, is an attempt at forging ahead with confidence, staying committed, not turning back. Nevertheless, it treads elliptically in fixed space; its lines circumvent, circumscribe, gradually discover, pull quickly away.

Thursday Mid-March: We Bury a Mouse

I wake in the morning with a familiar dread in my chest. I cannot remember dreams, but I do remember a startling, a shifting, a certain restlessness. Frank is already on the road, or at the gym. Somewhere in the days and miles past, Russia invades Ukraine; boy soldiers anticipating a camping trip in the snow find themselves instead prisoners of war. Buildings explode into rubble, antagonist and defendant argue over students. A Ukrainian farmer heists an abandoned Russian tank.

My paint palette is buried, color by color, in the spherical wells of two small plastic containers rubber banded together in the freezer. I get dressed in my warmest leggings, pin up my bedhead, find a stiff, non-drippy jam for Nora’s sandwich. Cut celery sticks, pear slices. Set a jar of ice water on the counter— no breakfast, just a good lunch and a cold drink. Nora doesn’t do breakfast.

I know the thing to do once Nora is gone is to walk fast, to find loveliness in the mountain’s shoulder, in the bare trees that reach for the sky. I do walk fast; at times I even run; and like Frank in his Tesla, I watch and listen. I see light filter, circumspect, around the ridged bark of trunks and branches, spread coverlet-like over the mountain’s shoulder. I listen to a podcast, to an apostle, hear calm, warm voices, catch and hold bright things I’d let slip.

The snake refuses to eat the mouse. They sleep together in his glass castle, a day and a night, the rumpled, thawed mouse– gray now, no longer cute– and the moveless, frightened snake, coiled up in his fake mountain rock. Nora calls it and asks me if she can bury the mouse in the garden.

We walk outside into the garden together; it is a graveyard of dormant promises. All the little babies I planted last year… I cannot tell how many have survived the winter. The sun today has warmed everything; the thawed dirt heaves up in pre-spring freedom. Our shoes sink gently down into the ground’s dry softness; it is wind-tousled feathers, the hem of a lifted skirt, a downy pillow, a thick comforter.

We pick a spot together at the base of a young rose bush: Madame Ernest Calvat, a Bourbon survivor. Her naked arms, unwrinkled, sprawl over and touch the ground. You can always bury any cast-off mice around my rose bushes, I tell Nora. I am trying to think in terms of compost and other gifts. I dig with my hands, deep into the warming soil at the feet of Madame Calvat, and Nora lays the rumpled, grey-brown mouse in its grave, and we cover it with dirt.